Napoléon’s Paper Veterans – Petits Soldats de Strasbourg

submitted by Eman M. Vovsi

submitted by Eman M. Vovsi

(the author is thankful to all Napoleon-Series contributors who mentioned in their posts, in different time, various paper soldiers’ collection discussed below)

Once upon a time, in a little town of Strasbourg, there was a baker/flour merchant named Christian Boersch (around 1780-1824) who painted charming little soldiers…

The story, which begins as a fairy tale, is not only true but enables us today to know the uniform worn by the thousands of men who passed through Strasbourg – France’s principal fortress facing Prussia – on their way to the battlefields of Europe. It was time when the streets of Strasbourg almost continuously resounded to the tramps of infantry shoes, the jingling of infantry harness, and the rumbling of iron-bound wheels of artillery batteries and supplies wagons. With the town population around 30,000 inhabitants, the permanent garrison ranged between 6,000 to10,000 men, above and beyond units constantly passing through the city. Not surprisingly, therefore, that some local armature artists, editors and book dealers, were inspired to try to capture this military pageantry and military drama in graphic form. When they were successful in so doing, their product found a ready market.

Boersch made and painted his paper miniatures with such care and detail that each figure seems to have actually lived the fantastic epic it represents. Little is known of this obscure Alsatian baker except that he was born at the outset of the French Revolution and died in 1861. His artistic development is attributed to the artistic development to the celebrated draftsman Benjamin Zix (1772-1811), whose niece Boersch married. Born in Strasbourg, Zix became known for his excellent painting of Swiss landscapes. In 1806 he was assigned, as a draftsman, to the Grande Armée HQ; at some point he also assisted famous Gros in his painting of the Battle of Eylau. Zix left us numerous sketches reflecting the every-day life of soldiers in their quarters in bivouac in Prussia, Poland and Spain, far different from the official salon painters.

B. Zis. French soldiers crossing the Danube, 1809

It was around 1810 that Boersch began painting his paper miniatures with the help of his uncle’s sketches and notes. Further, he was the first who invented the principle of mounting completed figures on wooden blocks. With the end of the Empire, Boersch interviewed retired soldiers living in and around the city, forming, little by little and with his son’s help, a fabulous miniature army lovingly conserved until 1971 in a local museum, when 4360 of his paper soldiers were sold at the auction in Angeres.

Boersch. Train d’artillerie de la Garde Impériale

Boersch. 9e régiment de Ligne

According to one opinion, the only figures which may properly be termed Petits Soldats de Strasbourg are those that were made by collectors who either:

– painted printed black-and-white sheets, or

– designed their own figures, had them printed and then painted them, or

– made each figure entirely by hand

In the case of printed sheets – whether engravings, woodcuts or lithographs – paper soldiers could be divided into three categories by the method of reproduction:

– First, editors who commissioned the artist and a printer to create sheets at the editor’s direction

Example: during the period of the First Empire one of them was certain Barthel of Strasburg, but majority of his works falls around 1820s. He was one of the first editors to complement his sheets of row-upon-row of soldiers with sheets portraying troops in a variety of occupation – in bivouac, fencing, or street life.

– Second, by painters acting as their own editors

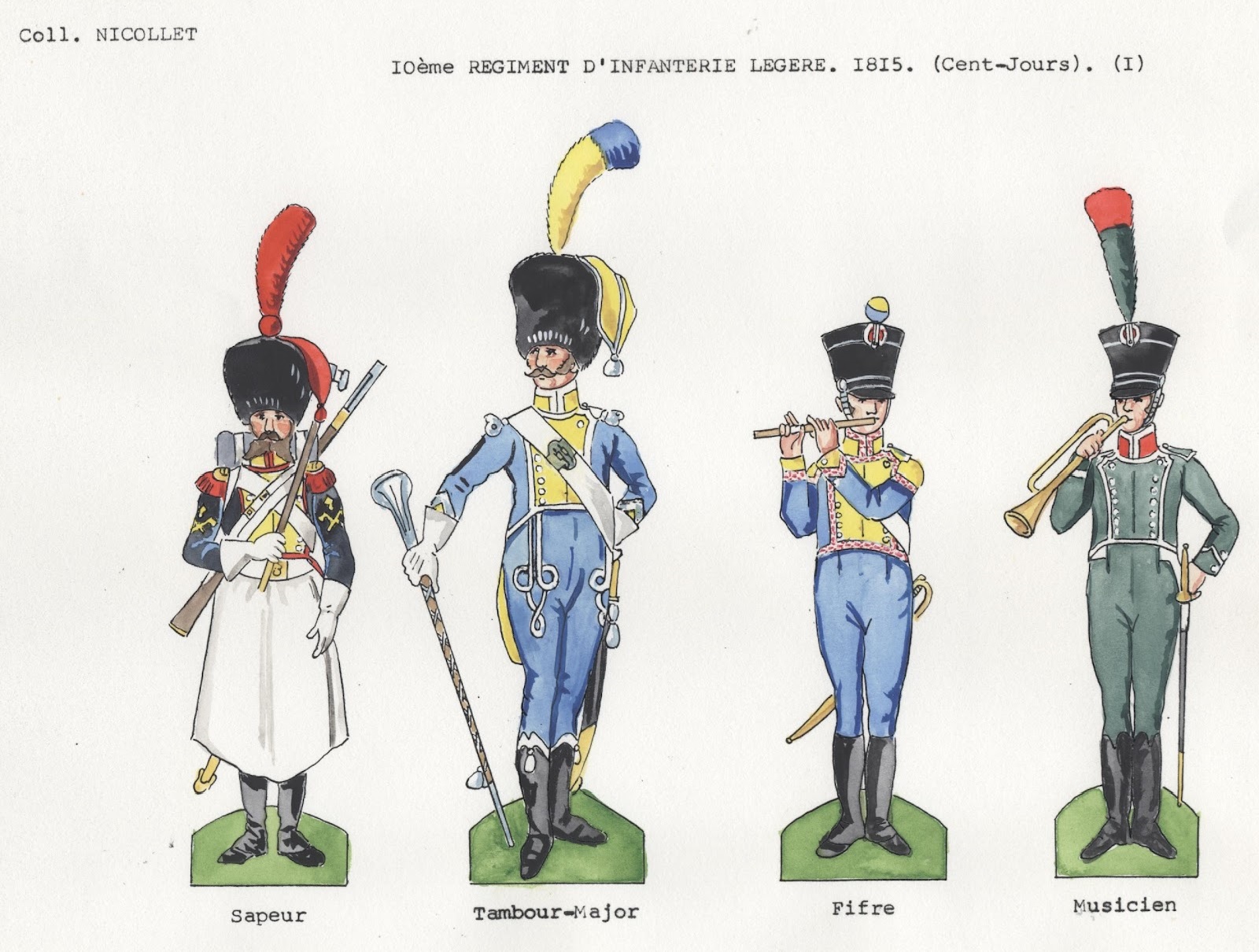

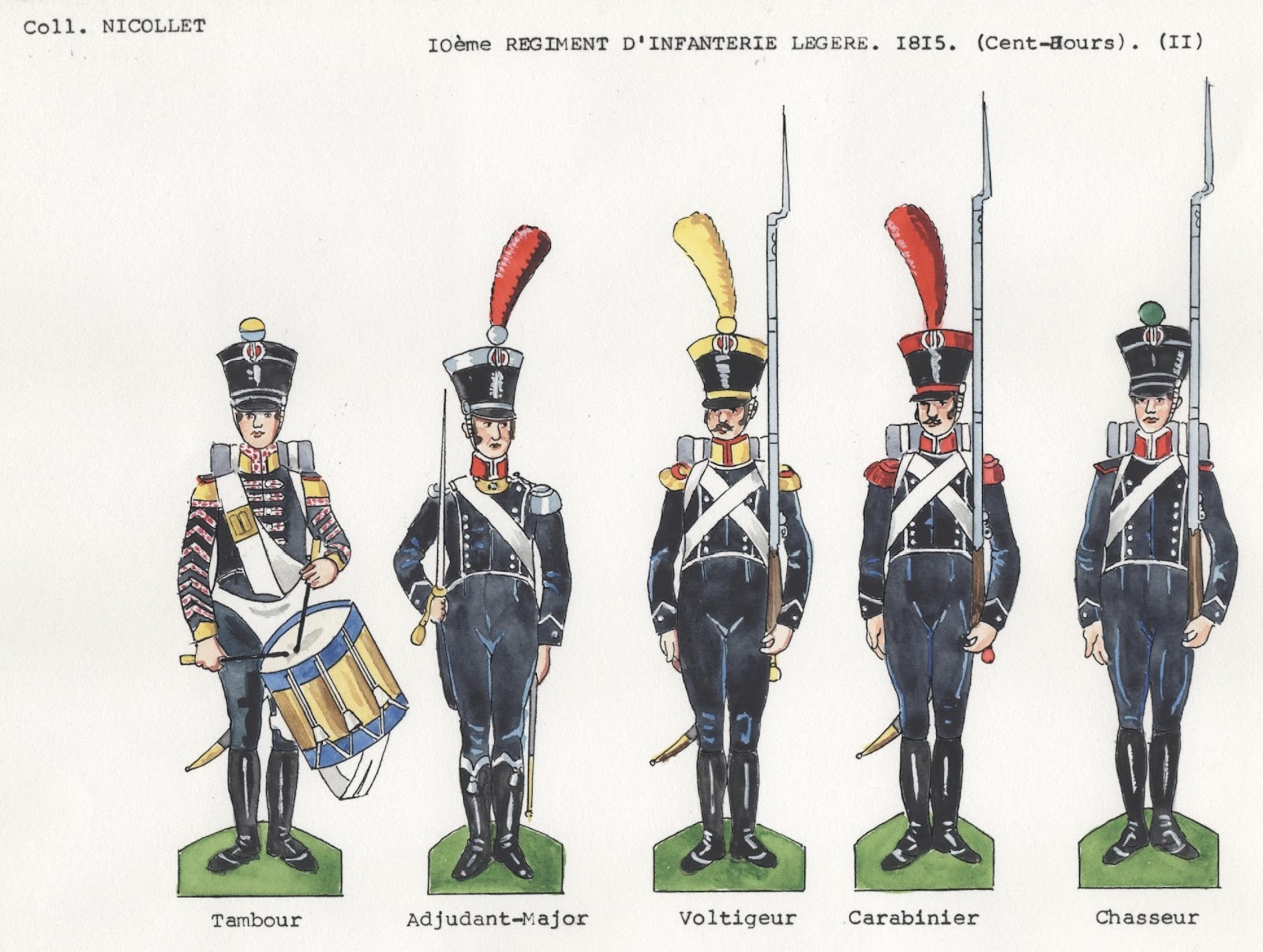

Example: Eugène Nicollet (1801-1865), an officer of the National Guard who, in 1817 has commenced his collection with his friend, Achille Roederer by painting his first soldiers and was continuing to do so for over 50 years. In common with a number of printers, he had a way of getting double use out of some of his designs of soldiers, by simply adding dotted outlines showing what, for example, a tricorn hat would look like instead of the bearskin cap that was the soldier’s “primary” headgear. In addition to designing his own figures, Nicollet also painted the printed sheets of Barthel (originally, published uncolored). Since Nicollet was at his late teens when he began his collection, his earlier works might contain certain mistakes or anachronisms.

Nicollet. 10e régiment Légers, is primarily showing soldiers wearing 1812 uniform Regulation as was reproduced by the French artist, Henri Boisselier (1881-1959) after the WWII.